You can’t solve everything at once

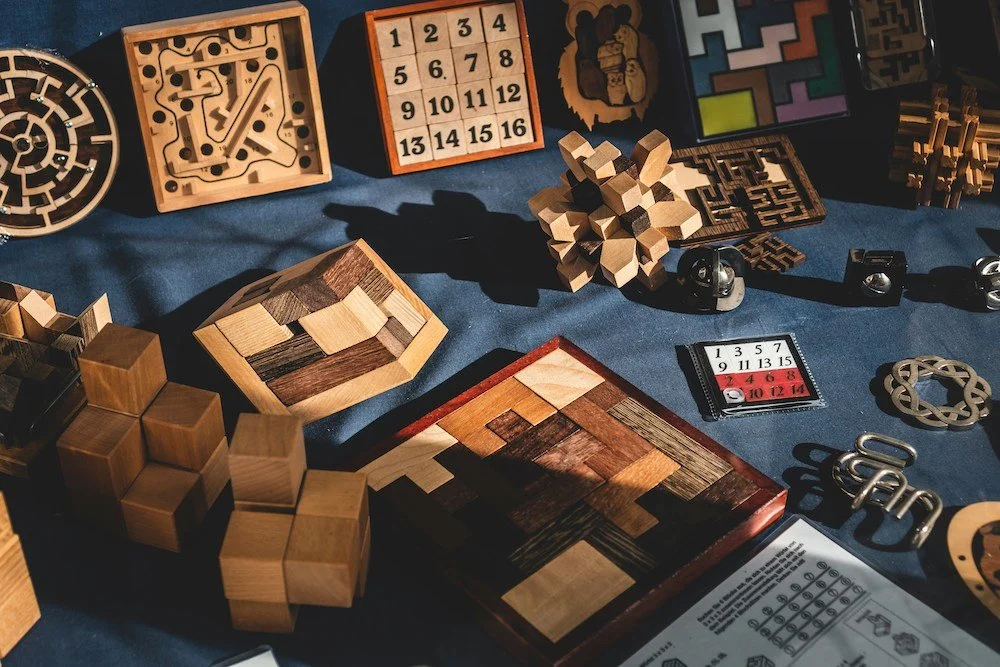

Photo by Jonathan Kemper on Unsplash

Last week, I wrote about a conversation I had with a student who was frustrated that the amount of effort they were putting into their work did not equal the resulting output. The hours (weeks, months) were there, but the student felt like they didn’t have anything to show for them. Part of why they were feeling this way was because they had started the project expecting that a single experiment would result in new, definitive insight into how something worked in the brain and mind. They kept trying new analyses on the dataset to see if something, anything, yielded the answers they were looking for. The problem? No analysis was actually going to yield those answers, because their experiment wasn’t actually designed to answer the student’s broad, ambitious questions. Instead, the experiment was designed as a first step to move a bigger research project down a particular path towards those ambitious goals. There needed to be several more experiments, from multiple angles of questioning and analysis, that could maybe then yield a guess at what was really going on in the mind.

Many students enter graduate school, or even their postdoctoral fellowships, with stars in their eyes. Their goal is to tackle big, interesting questions, and discover new insights, and to do so quickly. These are admirable and lofty goals, but the bulk of scientific findings come from years of incremental and programmatic research. You don’t solve everything all at once. And that’s actually part of the magic of science. Each experiment reveals a finding—a little nugget of knowledge or a curiosity—that then leads you to the next question that you couldn’t have even imagined before. Then you design the next experiment to tackle that question, and the cycle starts again. Even when experiments don’t ‘work’ as predicted, the data are telling you a story that, if you pay attention rather than dismissing it, can lead to the next insight, that you can test with a new study. This is what one of my colleagues calls strategic patience. You keep your eye on the prize, your bigger vision and the field of study that interests you, but you chip away at it, knowing that each step brings you closer and closer to where you want to go. Or, as a friend of mine, an avid distance runner likes to say: forward is a pace.

To illustrate this point, let me give you a sports analogy, specifically from baseball. Last month, you may have watched the Toronto Blue Jays play the LA Dodgers in the World Series (and if you were from Canada in particular, you watched your work productivity decline as a result, but I digress). There were games that were won by home-run dingers, but there were also games won by playing small ball: keeping the runners moving by getting base hit after base hit, or by leveraging outs as resources that can be turned in valuable runs, or by using bunts to move a runner from second to third. Science is a lot like baseball in this regard. You can get big wins by playing small ball; conducting sets of experiments that incrementally build on each other to ultimately give you a win. And, even those home-runs—which look a lot like solving everything all at once—actually come from hours and hours of working on the swing, studying the pitcher’s approach, and practicing emotional regulation to meet the demands of an intense, pressure-filled moment. Like a solid swing that sends the ball over the left-field wall, those new and shiny scientific breakthroughs don’t really come of out nowhere; they come from consistent effort that meets opportunity.

But more importantly, you don’t have to swing for the fences every time. Science rewards those who play the long game, those who stay curious, consistent, and open to where each experiment leads. If you’re feeling stuck or impatient with your progress, I can help you create a roadmap that keeps you moving forward, one small win at a time. Book a free discovery call here so you can build momentum toward your next big breakthrough.

Next week: You don’t have to solve everything to get a job